There’s an old saying you might hear when you arrive in Seychelles — that if you eat the breadfruit there, a return trip is guaranteed. A few hours after I arrived, I was nibbling on a plateful in the restaurant of Le Jardin du Roi, a spice plantation on Mahé, the country’s largest and most populous island. The fruit tasted like a delicately sweetened sponge. But as I ate, coming back was the last thing on my mind; I was focusing on how to stay positive. After my plane landed in Victoria, the capital, I was met with the kind of slashing wind and rain that dislodges coconuts from palm trees, flips umbrellas inside out, and dampens the heart of a writer who has just travelled 15 hours from gloomy, Omicron-ravaged Paris (a stopover on the journey from New York). By Marcia DeSanctis

On a map, the 115 islands that comprise Seychelles are tiny dots in the Indian Ocean, about 1,000 miles (1,609 km) east of Kenya. (More than a third of them are formed from granite, indicating that the country was once part of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, which later broke apart to form South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and parts of Asia.) This extreme remoteness means that the country remains a mystery to most travellers. But even in a downpour, I was beginning to see why 24 hours of air travel was worthwhile.

Here’s why Seychelles is the perfect beach getaway

An aura of sensuousness struck me as I checked in to my first hotel, the Four Seasons Resort Seychelles, where the entrance was dominated by what appeared to be wooden sculptures of the female derriere. In fact, they were the dried fruits of the coco-de-mer, a species of palm found only in Seychelles. The fragrance of cinnamon, frangipani, and mango, which grow wild on the property, drifted in the air.

My villa, perched high on a hill, had a tub with an ocean view of such spectacular drama that I immediately drew a bath to try and take it all in. Through the floor-to-ceiling bathroom windows, I could see the tempest frothing my private swimming pool. I tried to quell any lingering anxieties about the weather and resolved to swim anywhere water presented itself on this trip, rain or shine.

My nine-day itinerary was a whirlwind, planned with rigorous precision by Africa specialist and T+L A-List advisor Cherri Briggs and her crew from Explore, Inc. Most visitors to Seychelles book a single property and stay awhile, but I took the lay of the land by visiting five islands and six hotels in one turbocharged adventure.

Though Seychelles covers only 150 square miles (388.4 square km) of total landmass, its national borders encompass some 5,00,000 square miles (1294994 square km) of water. The country is, essentially, a large oceanic state. “You can see why we are uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change,” Helena Sims said over breakfast on Mahé. A Seychellois marine biologist, Sims works with the Nature Conservancy, an environmental nonprofit with outposts around the world—including a significant presence in Seychelles.

Among the effects, Sims described were coastal erosion and, more startlingly, coral bleaching. When sea temperatures rise, coral become stressed and expel the algae that give them their colour and are crucial for their survival. Several mass bleaching events were considered so grave that, in 2015, the Nature Conservancy brokered a groundbreaking “debt for nature” swap. Through a combination loan and grant, the group provided the Seychelles government with enough money to pay off USD 21.6 million (INR 1,64,05,52,400) of its sovereign debt while also financing projects to protect the country’s marine environment. The problem is existential: tourism and the fishing industry are the pillars of the economy, and the country’s 1,00,000 people depend on a healthy marine ecosystem for their livelihoods.

“The voice of the islanders is getting stronger,” Sims said. “The Seychellois are really driving the discussion, especially when it comes to putting other countries to task.”

A working-class Seychellois woman narrates Coco Sec, a 1977 novel by the country’s most celebrated author, Antoine Abel. The book, which I read before my trip, begins with a 13-page glossary of Seychellois Creole words, including calou, a fermented drink made from the sap of a coconut blossom; fataque, a plant used to make brooms; and la zourite, which means octopus—a mainstay of the islanders’ diet. Though English and French are official languages, everyone speaks Creole (Seselwa), a French derivative with Bantu and Malagasy influences.

It wasn’t until the 18th century that settlers arrived in the Seychelles, which had no indigenous population. Arab geographers first wrote about the islands in the tenth century, and in 1502, Vasco da Gama charted them on behalf of the Portuguese. For much of the 17th century, the Seychelles were left largely alone. But in 1770, French settlers arrived and began to exploit the archipelago—which was named for King Louis XV’s finance minister, Vicomte Jean Moreau de Séchelles—for vanilla, coconut, cinnamon, and sugar. Those first settlers brought with them seven enslaved people from East Africa. Over the decades that followed, thousands more were brought in to labour on plantations. In 1814, after the Napoleonic Wars, Seychelles were ceded to Great Britain. Six thousand people in all were transported to the islands as part of an economic model that ended with the abolition of slavery in 1835. In 1976, the country declared its independence from Great Britain, though it remains part of the Commonwealth.

“We are one of the most unique cultures in the world, and it is our duty to promote and strengthen it,” said cultural historian Emmanuel d’Offay. We were walking through an exhibition space in the National History Museum, which occupies the colonial-era Supreme Court building in downtown Victoria. Garments, tools, and old photographs were part of a display detailing the origins of his people. “We are French; we are Indian; we are African. But we are all Creole.”

In the 19th century, British colonialists adopted the Indian rupee, which is still the country’s currency. Malay exiles and Arab and Chinese merchants exerted their influences, too—in music, cuisine, and religion. Over centuries, these races, ethnicities, and cultures layered, mingled, and intermarried (sometimes by force), resulting in a society of stunning diversity.

When I stopped at the busy Victoria Market, Seychellois of all skin tones were working the stalls behind towers of jackfruit and papaya. Hymns burst from the Anglican cathedral nearby, and a clamour of drums and bamboo flutes played outside the Hindu temple.

What seemed like monsoon conditions made the Beechcraft 16-seater bounce as it headed toward Desroches, about 145 miles (233 km) southwest of Victoria. We landed on a tiny airstrip that, on dry days, doubles as the island’s yoga studio and soccer field. The storm finally subsided as I checked in to the Four Seasons Resort Seychelles at Desroches Island, the brand’s second property in the country. It’s the only hotel on the island, and almost all the residents are employed by the resort or by the Island Development Company, an organisation created by the government to look after the well-being and infrastructure of outer islands like Desroches.

After I got to my villa — one of 71 on the 117-acre property — and finished my vanilla-laced iced tea, I changed into a swimsuit and stepped out onto a palm-studded, powdery beach. It was so pristine, so perfect, so “all mine” that I charged right into the surf, where I floated like driftwood for what felt like hours.

Later, I hopped in a golf cart with Babu Kinjarapu, an engineer at the hotel, who showed me the vast installation of solar panels that power virtually the entire island. We bumped through lush forest as humid as a steam shower. “We like rain!” he exclaimed, echoing almost everyone I had met so far. “It makes the dust settle, and look how green the jungle is.” Point well taken.

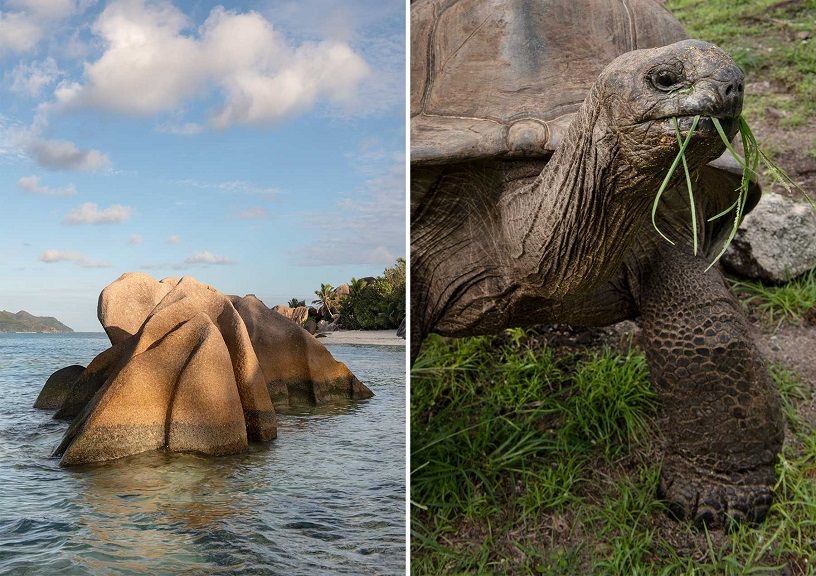

Our next stop was the breeding sanctuary of the Aldabra giant tortoise, which is funded by the Four Seasons. The population of these creatures had been decimated after centuries of hunting by European settlers, who used them as a food source. In 2011, the gentle, endangered giants were introduced to Desroches. Now some 150 of them roam free on the paths and in the forest. A 300-pounder leaned into me as I stroked his elongated neck with one hand and fed him mulberry leaves with the other.

The next morning I awoke to brilliant sunshine, the sky purified by storms. I hopped on my hotel-provided bike and explored nine miles (14.4 km) of the island’s sandy paths, pedalling barefoot in my bathing suit, a towel draped around my neck—freewheeling in a way I hadn’t done in decades. There was that perfume again. Vanilla, coconut, salty air, something flowery. Sunshine scorched the tops of my hands, and I stopped for a dip at every beach (five in all). The most beautiful was Madame Zabre, a pale crescent of sand lapped by curlicues of crystal sea.

After my ride, I met with Jean-Claude Camille, a Seychellois biologist and a senior officer for the Island Conservation Society. He seemed to know every living thing on Desroches. He described the considerable efforts of his organisation, which is funded in part by the Four Seasons, to protect the island from tidal erosion. Desroches is an atoll—formed by a sunken volcano. Winds and currents shift their contours, as do rising sea levels caused by global warming. “Nature is not happy,” Camille told me, “when man makes a mess of things.” During the full year the hotel was closed because of the pandemic, he helped erect a retaining wall to stave off more significant damage. He pointed out a red-plumed Madagascar fody warbling for a mate, then scooped up a zanmalak and tossed it to me. I crunched into the sugary, watery fruit, which resembled a pinkish pear.

The next few days were an island-hopping blur. I returned to Mahé to board the first of two ferries to the island of La Digue. The air smelled of diesel smoke, and the passengers sat cheek-by-jowl. Fortunately, mask wearing was strictly enforced. Smashed by the wind, pummeled by a brief cloudburst, I disembarked from the second ferry and found my guide, Yacinte Jacques, waiting in his scarlet golf cart.

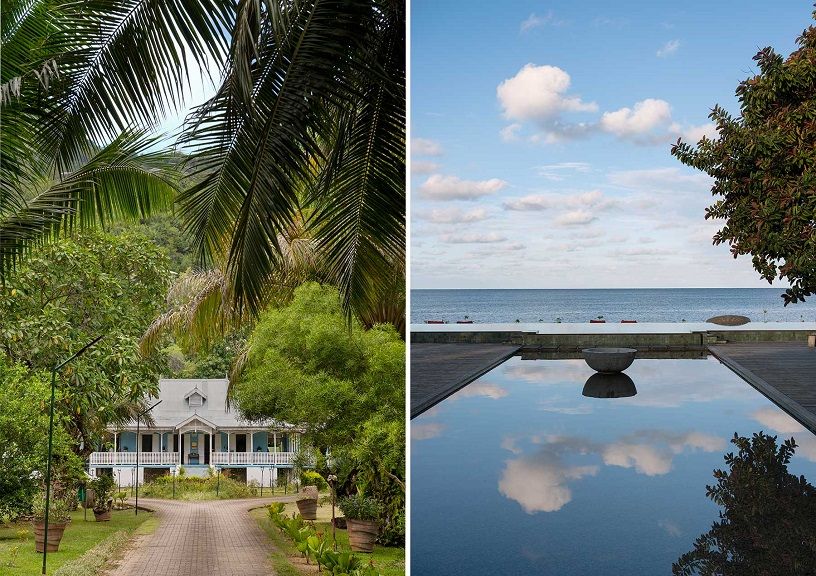

As we drove around the laid-back streets of La Digue, Jacques told me he was born and raised on this island of 3,500 people. The city’s pastel-hued downtown is made up of one narrow street and—fortunately—an ATM. I had been tipping more than usual, given how ruinous COVID had been to the tourism industry. Jacques drove me to L’Union Estate, a colonial-era farm with the largest vanilla plantation in the Seychelles. This adored flavour starts life as a wild rainforest orchid. As I held a firm, unripe bean, I considered the long journey it would potentially take from the island to someone’s blonde brownies, but the moment was interrupted by Jacques, who told me to look up. Above the treetops rose a 130-foot-tall monolith. It was granite, but its folds looked velvety. We headed down to Anse Source d’Argent, one of the Seychelles’ most legendary beaches. I waded in and out of tide pools and threaded between smaller versions of these majestic boulders, which had been shaped only by water and time.

My thatched-roof villa at La Domaine de l’Orangeraie was surrounded by lemongrass and makrut lime trees. I could finally identify the three-veined leaves of the cinnamon tree and crunched a handful, the pressure releasing the warm smell of something baking.

At dawn, Jacques shuttled me to Grand Anse, a beach on the eastern coast of the four-square-mile (10 square km) island. Some clichés in life are deemed so because they are perfect; I revelled in one as I bathed in the Indian Ocean while the sun rose over it.

The next morning, I ferried to Praslin Island for lunch and a walk through Vallée de Mai, a forest of coco-de-mer. The female fruit resembles a pair of life-size buttocks, but there is a male version, too (this one resembling — you guessed it — a penis). Both were so anatomically correct, and overtly suggestive, that I hesitated to touch them. The fruit’s primordial sensuality convinced British general Charles George Gordon, during an 1881 visit, that he had found the “forbidden fruit” that Adam and Eve had consumed. This is why Seychelles is at times referred to as the Garden of Eden.

Back in Mahé, I arrived, weary, at our overnight port of call, Carana Beach Hotel. I had wheeled my bags across plenty of docks and gangways that day, so I needed exactly what this luminous hideaway delivered. A snoot of local rum, laced with — what else? — vanilla, a smashing Creole dinner (rock lobster, sweet potato, and cassava galette), and turquoise waves to leap into at daybreak.

A few hours after my morning swim, I was choppering the 18 miles (28.9 km) from the hum of Mahé to the pristine isolation of North Island. Below us trawlers cast their nets for tuna. The industry brings crucial revenue to the country, but those nets are often discarded, which can be catastrophic to wildlife. In fact, the Seychelles government is under pressure from watchdog organisations to mitigate the harm and to demand that the worst offenders pay fines for the degradation these nets inflict. The pilot pointed out a whale shark swimming in water so transparent we could see the creature’s spots.

Many celebrities had travelled that route to North Island before. George and Amal Clooney and Prince William and the Duchess of Cambridge reportedly honeymooned there, and I could see why they’d appreciate the low-key decadence of this 11-villa resort, which was built in 1997 and is now part of Marriott’s Luxury Collection. My appointed butler, a Sri Lankan named Janaka Dodanwala, was somehow able to intuit how I liked my coffee when I might be hankering for fresh mango, or that a ginger-scented bath might be in order — even after a long day of doing practically nothing.

I strolled up and down the beach, relishing the memory-foam spring of the sand. Whenever I had the urge, I sidled into the ocean to rinse off. One day, I accompanied Dominique Dina, the 23-year-old Seychellois ecologist who heads the island’s conservation team, on his beach patrol. “Our job is to restore North Island to its former glory,” he told me, referring to the removal of animal and plant species imported during colonial times. He spoke passionately about the at-risk sea turtles, which he tags and monitors, and the Seychelles white-eye, an endemic bird that has been successfully reintroduced.

I wore shoes only once, to climb a hill to get a better view of the beach that paints a white circle around the forested island. The horizon was cloaked in rain clouds, and the downpour was just long enough to burnish the palm leaves and churn the fragrance of the white takamaka flowers — reminiscent of gardenias — that grow in profusion.

One morning I snorkelled, drifting above rainbows of tropical fish. Each day, I ate magnificent meals of fresh tuna, octopus, and incomparable giant prawns, as well as sticky desserts spun from bananas, star fruit, guava, and coconut cream. Gradually, I unwound, luxuriating in this principality of bent palms. It was not just island living; it was private island living. I slept well and dreamed good dreams.

At the Piazza, which is what the resort calls the breezy outdoor common space, I chatted with the deputy general manager, Nicolas Louys. Seychelles went into full lockdown for three months in 2020, and once the borders reopened, business was steady. Their well-heeled, international clientele returned because they love the island’s remoteness and privacy. “It’s an easy place to be during a pandemic,” Louys said.

I had pondered something during my long flight. Surely there are scores of places with white sand, celadon seas, and soothing trade winds that are easier to get to? At that, Louys waved his hand toward the vista, a spectrum of pale blues and greens. “The feeling in the Seychelles is different than any place in the world,” he said. Something, I noted, that other islands might also claim. The 31-year-old Seychellois continued: “I think the sense of abundance comes from my Creole people. We live in the most beautiful country in the world, and we really believe in it.”

It was, in fact, part of the story. This distant place was a true crossroads. A culture arose that was both one of a kind and thoroughly global. The other obvious truth: the long voyage to get there only heightens the allure. As do the tender affections of something that can only be experienced in Seychelles — a 300-pound Aldabra tortoise.

After two final boat rides — about two hours in all, plus a drive from the port to the hotel entrance—I arrived at my last destination, Anantara Maia, which occupies a peninsula on the western coast of Mahé. Like the other properties I visited, the hotel offered faultless service and pristine, empty beaches.

At the Maia, there was a sultry spa with outdoor treatment rooms that seemed to spring from the jungle. It has a private pool I knew I would dream about all winter while scraping ice from my car. I took in the view of Anse Boileau and suited up for a penultimate swim at the beach. Tanned and a little spent, I was a calmer woman than the one who arrived, sulking, in the rain. In this fascinating, diverse, and dreamlike utopia, I had found vitality and repose.

Before my flight home, I joined a few hotel employees on the sand for one last sunset. We raised our glasses to safe passage and the bittersweet end of a beautiful journey. As we did, I took some salty snacks from a wooden bowl. “What are these?” I asked, munching. They were breadfruit chips.

Because everyone knows you can’t take heaven with you, but you can always come back.

Diving into Seychelles

Where to Stay

Anantara Maia Seychelles Villas: This Bill Bensley–designed compound on Mahé has 30 thatched-roof villas dotted across 148 acres of jungle, and each has its own infinity pool. Doubles from USD 3,025 (INR 2,29,735).

Carana Beach Hotel: Five miles (8 km) from the capital, Victoria, this beachside property offers 40 airy chalets. It is one of the best values in the Seychelles. Doubles from USD 580 (INR 44,048).

Domaine de l’Orangeraie: The resort’s 63 villas are situated in lush, tropical gardens on the island of La Digue, with a stunning west-facing pool perfect for viewing the sunset. Doubles from USD 600 (INR 45,567).

Four Seasons Resort Seychelles: It’s located high on a Mahé hilltop, so rooms have endless views of the Indian Ocean. A private, powdery white-sand cove awaits below. Doubles from USD 1,560 (INR 1,18,474).

Four Seasons Resort Seychelles at Desroches Island: A tiny coralline island with no cars, Desroches has its own airstrip and a low-key yet unerringly five-star environment. Doubles from USD 970 (INR 73,667).

North Island: A private island favoured by celebrities, this 11-villa resort is known for a sense of pampered seclusion. Doubles from USD 2,350 (INR 1,78,471).

How to Book

This trip was planned by T+L A-List member Cherri Briggs, an Africa specialist. Briggs and her team at Explore, Inc. can create a personalised itinerary, which might include diving and bone fishing—two activities for which the Seychelles is known—with expert local guides. Five-night trips by Explore, Inc. from USD 15,000 (INR 11,39,182).

Related: This Hotel On A Private Seychelles Island Has Its Own Runway For Stargazing