Just a few years ago, gorillas were the only draw for visitors to irrepressibly beautiful, once-war-torn Rwanda. Today, the country’s diverse wildlife—from silverbacks and chimps to the Big Five—makes it not only one of Africa’s great safari destinations but also one of its most inspiring conservation success stories. Text by Marcia Desanctis. Photographs by Ambroise Tézenas

My first morning game drive at Magashi Camp had begun uneventfully. Snug in a fleecy poncho after a brief thunderstorm, I sipped a mug of coffee as our guide, a 28-year-old South African named Adriaan Mulder, offered up the standard commentary from the driver’s seat: “Those are topi antelope. They can run more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) an hour.” Warthogs scooted for cover, and velvet bush willows shone iridescent from the rain as our vehicle slurped through gullies of mud, bumping along through Magashi’s 15,000-acre chunk of Akagera National Park, in Northeastern Rwanda.

Suddenly a voice came crackling over Mulder’s two-way. It was one of Magashi’s trackers, who monitor wildlife on the concession. Mulder did an abrupt U-turn, then looked over his shoulder and said, “I’m actually shaking now.”

As we rounded a curve in the road, it became clear why. Standing stock-still on the grass, against a billow of retreating thunderclouds, was a lone rhinoceros. “It’s Mandela,” Mulder whispered, his voice tight with emotion. Then: “You are the first person ever to see a rhino in the wild at Magashi.”

Mandela, a four-year-old eastern black rhino, was born in a safari park in Denmark. Four months before my visit, he had arrived in Rwanda, the culmination of an epic translocation project designed to repopulate Akagera, which is still healing from decades of war, poaching, and neglect. As he grew accustomed to a new life in his natural habitat, Mandela had been slowly working his way out of a series of enclosures, and that morning, he was finally confident enough to venture into the grassland to face predators and forage for food. The eastern black rhino disappeared from Rwanda in 2007; Mandela’s formidable presence in the reserve declared, We’re back.

He seemed relaxed but smartly bolted for a thicket when, several minutes later, a hippo came at him like a brake-less truck. Still, I was worried. Preservation instincts are one thing, but the bush cares nothing for the emotional state of a new kid in town. “Mandela’s strong,” Mulder reassured me, “and ready for anything.”

As Mulder absorbed Mandela’s triumphant re-entry into the wild, I was doing some processing of my own. Pocket-size Rwanda— a nation that just 26 years ago was the site of one of the worst genocides in history—had successfully restored this spectacular wildlife reserve. For the first time in two decades, the Big Five (rhinos, elephants, Cape buffalo, lions, and leopards) once again graze and hunt there in primordial bliss.

I first travelled to Rwanda in 2011 to work with an NGO, staying in basic guesthouses and crossing the country in overflowing local buses. Even then, I was amazed by how optimistic and secure the country seemed, considering it was only in 1994 that an unimaginable one million Tutsi were massacred by the Hutu majority, leaving the nation’s infrastructure, economy, and society in tatters.

Now that sense of optimism was everywhere I looked. I was on a high-end safari, swaddled in every comfort—from the top-of-the-range 4 x 4 to the “Dior pink” mosquito netting in my sleek private tent at Magashi. And I was on the road with Micato Safaris, the family-run outfitter whose meticulous attention to detail has earned it a reputation as the gold standard in safari tourism.

Magashi was the first of a trio of plush new properties on my itinerary, each in very different national parks. “In the past, people only thought of gorillas,” said Anita Umutoni, 31, manager of Magashi, which is the second Rwandan lodge from luxury outfitter Wilderness Safaris. “Now that’s changed. We also have chimps, rain forest, big game, volcanoes—and people can see it all in a few days.”

It’s true that until very recently, most visitors to Rwanda would fly into the capital, Kigali, zoom up in a helicopter or car to Volcanoes National Park to see its legendary mountain gorillas, then fly off to view the Big Five in Tanzania or Kenya. But, just as the country has defied all expectations with its miraculous rebirth, social innovation, and economic development, now there is a new set of goals: to offer travellers a rounded experience, one that goes far beyond primates, and to attract the visitors who give back the most.

Back at Magashi after my memorable morning safari, I sat in the shade of an albizia tree and sipped tree-tomato juice (which tastes like a mix of papaya and kiwi) with Umutoni. When I arrived the previous day, I immediately had the feeling we’d met before. It turned out I had interviewed her nine years ago when she was studying hospitality in Kigali.

Back then Umutoni had told me, “My dream is to contribute something important to my country.” Today she is a seasoned pro running a flagship camp for one of the biggest names in eco-tourism. As we looked on, a trio of elephants splashed in the shoals of Lake Rwanyakizinga. “Our energy comes from a real desire to build our country—and build it ourselves,” she said.

That effort doesn’t always come without a cost. Rwanda’s progress has been overseen by former rebel general Paul Kagame, who has been president since 1999. He has emerged as one of the world’s most disciplined and ambitious leaders, presiding over Rwanda’s transformation from an agrarian economy to one based on tourism, business, tech, and science. But his increasingly authoritarian ways have made him both quietly feared in his own country and a target of global human rights organisations.

Out in the bush that afternoon, giraffes leaned over the roads cutting through Magashi’s property and shot us bemused stares. Candelabrum trees threw their fingers to the sky, and knob wood released its tangy lemon scent on the breeze. From a nearby thicket, a couple of intense Dugger Boys—the regional nickname for older Cape buffalo—shot me a withering gaze.

As we drove, Mulder told me how the reserve had come to be anointed as Rwanda’s latest success story. In 2010, the government partnered with African Parks—a non-profit conservation organisation that manages protected areas throughout the continent—to repair and rebuild Akagera, Rwanda’s only protected savanna ecosystem. At the time, the park was struggling. Farmers returning from exile following the genocide had moved in with their cattle, which led to overgrazing and other ecological problems, as well as to the total extinction of lions from the reserve.

In 2013, a fence was erected around the park, helping to minimise human-animal conflict. Two years later, lions were reintroduced, and today 40 of them prowl, roam, and laze about Akagera’s 1,122 square kilometres of riverine forest, grassland, and wetland. One afternoon, we counted 11 posted in a tree, which shook as they swatted flies with their tails. Three nursing cubs tumbled over one another, while a mother and daughter lay in the spoon position, their paws like big loaves of bread.

In 2018, Wilderness Safaris obtained the concession to build Magashi Camp. Among its tasks was to bring experienced hands like Mulder’s to carve roads for game drives, set up guiding standards, and teach the local team the difficult balancing act of keeping guests delighted while simultaneously keeping them safe. “Slowly but surely, we are passing on all this knowledge to Rwandans,” Mulder said.

As the day drew to a close, we motored on Lake Rwanyakizinga in an aluminium swamp cruiser, stopping for a sundowner blended with sweet Rwandan rum. A full moon hoisted itself over Magashi and made the lake glow like platinum. Back on shore, a campfire awaited us, as did the percussive brays of a nearby pod of hippos.

On my third day in Rwanda, Micato arranged for a helicopter to ferry me to Volcanoes National Park and the new Singita Kwitonda Lodge—named after one of the 10 mountain-gorilla families that inhabit the nearby slopes of the reserve. My safari director, Peter Githaka, who accompanied me on my entire trip, ushered me on board the chopper with his customary calm. Based in Nairobi, 33-year-old Githaka is one of Micato’s most experienced hands. Somehow, he found out in advance of my arrival that I loved Peanut M&M’S, so he kept the snack bin of the gleaming Toyota Land Cruiser stocked. He worked with the hotels to arrange bespoke activities, and when I peppered him with questions, such as “What is that bird we hear?” he unfailingly knew the answer.

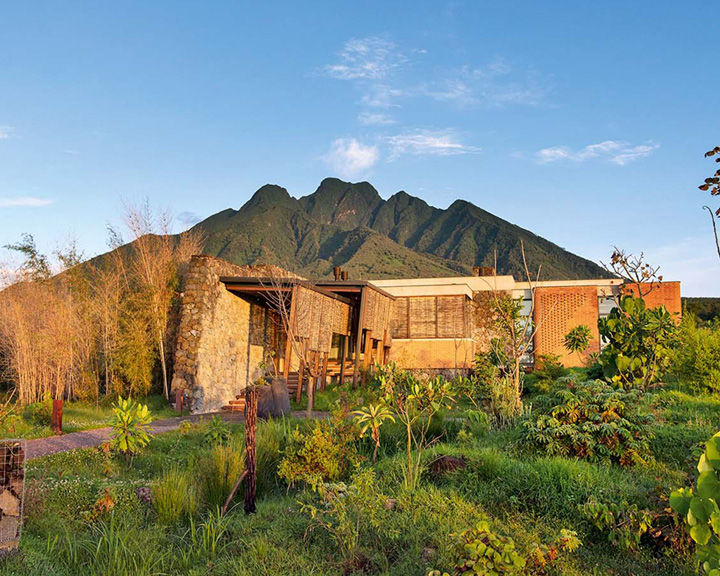

We floated up above Akagera like a bubble. Airborne in leather seats, we could see many of Rwanda’s storied hills: some rocky and black-shouldered, others softly sheathed in forest foliage. Behind them rose the brooding volcanic peaks of our destination, the Virunga Mountains. Kwitonda is the first lodge in Rwanda from the South Africa-based Singita group. Like all the luxury hotel operators in the country, Singita works closely with both the national park and the local population. More than 600 community members were hired to build the property, which was made of igneous rock quarried nearby and cut into blocks on site. “Our hope is to disappear into the jungle one day,” said Kwitonda’s manager, a South African named Brad Murray, who oversees a mostly Rwandan team. The roofs of the nine private villas are planted with orchids and other indigenous flowers that form micro-habitats for butterflies, bees, and birds.

There is no other way to say it: Singita is gorgeous. Through the picture window of my suite, I watched fog glide over meadows of canary-yellow wildflowers and brush the jagged tooth of Mount Sabinyo, one of five volcanoes in the park. The common rooms are a ramble of tactile fabrics and velvet-smooth stone, and abundance was everywhere: platters of fresh mango, endless tart Rwandan coffee, and a dizzying line-up of South African gins, mixed with tonic and served wordlessly when the staff sensed what I was eyeing from the all-day bar.

But the beasts beckoned, and so, clad in moisture-wicking finery from Singita’s gear room, I ventured out to meet Rwanda’s famous primates. “Are you ready to see the gorillas?” asked our Rwandan trekking guide Jolie Mukiza, one of just three female guides at Volcanoes. She and the rest of the team wore only flimsy rubber boots. “Are you sure that’s enough?” I asked as I clambered over roots in my high-performance footwear. “I’m very used to it,” she said with a smile.

Volcanoes is Rwanda’s flagship park, and it leads the way in conservation tourism. After the genocide, Rwandans realised that the country’s wildlife habitats were the key to prosperity: if the animals were properly protected, then tourists would pay dearly to see them. But for this to work, the government needed to limit environmental impact by keeping prices high. “A large footprint not only spoils the environment but ultimately will spoil the tourism industry,” according to Linda Mutesi, tourism marketing manager for the Rwanda Development Bureau.

Just 96 gorilla-trekking permits are issued each day. Each now costs around `1,13,470, creating an increase in income that means strengthened preservation efforts for the gorillas and their habitat, as well as more community programmes, which receive 10 per cent of all tourism revenue. Over the past 20 years, the population of gorillas in the Virungas—which straddle Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—has doubled to 1,064. Though work to protect the species continues, it is now off the critically endangered list.

After an hour’s trek, we heard the loud snap of bamboo breaking. One last push and there was the Kwitonda family, scattered in assorted acrobatic poses. A baby trampolined off his mother’s tummy onto a branch. A blasé adolescent male slicked back his pompadour. The family’s dominant male, 225 kilograms of the silverback, rested his chin on his fist and yawned. A puffball of a toddler wobbled toward our group, and my arms twitched, so badly did I want to scoop up the little creature with whom I share 98 per cent of my DNA. As babies frolicked and mothers indulged, it occurred to me that the gorillas’ expression of elemental human behaviour is why we rejoice in these animals, are moved by their presence, and applaud Rwanda’s commitment to saving them.

We left the Virungas and headed south to Nyungwe Forest National Park, driving past the massive Lake Kivu and the smoking crater of Mount Nyiragongo, just over the border in the DRC. Nearly every mile of the landscape was draped in an emerald necklace of pastures, farms, and banana groves. Our driver, Ismael Nsengiyumva, 32, told me he survived the genocide by hiding under corpses in the city of Ruhengeri, located in the province we were just leaving. He was seven years old. Nsengiyumva relayed the story dispassionately but omitted no details. I asked if telling it was difficult. “No, not anymore,” he said. “But I hate it when people still think of Rwandans as killers and victims.”

I had noticed that Rwandan people brought up the genocide less each time I visited, saving their collective grief for the anniversary of that harrowing event each April. Today, Rwanda’s trauma seems to be a motivating force rather than the burden it might have been. But it would be callous to separate the legacy of genocide from the people who were—and still are—broken from it.

We detoured for sambaza―tiny fish fried until crisp―at a lakeside inn in Kibuye. Some of the bloodiest atrocities were carried out in this town in 1994, and we stopped to bow our heads at a mass grave site, one of the hundreds in the country.

By mid-afternoon, we turned onto the red clay road leading into One&Only Nyungwe Forest Lodge, which sits in the middle of a chlorophyll-rich tea farm. The leaves of its bushes still shimmered from rain. There are four tea factories on the periphery of Nyungwe Forest National Park, and the micro-climate nurtures high-quality leaves. At lunch, I ordered an excellent tea-leaf-pesto pasta and considered the fact that my luxurious excursion around Rwanda was made all the more complete by the country’s impressive geological range. In Nyungwe, the landscape felt refreshing and alive. In the distance, I could see mist clinging to the forest, the oldest in Africa.

Nyungwe House was bought by the One&Only group in 2017 and refurbished by the German-born designer Hubertus Feit, who told me about his vision for the property over a glass of wine by the pool. “Look,” he said, pointing to the landscaping around the property, “A perfect line of green beside a million-year-old forest.” Indoors, he emphasised soft, earthy beiges and browns. “Everything is downplayed to make you look outside. You don’t need anything else. The strength of these green hills is just unbelievable.”

We made another early start the following morning, setting off on a trek through the cloud-draped forest. But this time, I was on the lookout for chimpanzees, roughly 500 of which live in the Nyungwe Forest—one of just a handful of places they can still be seen in their natural habitat. Nyungwe is home to 13 species of primates; as we set off, saintly-faced black-and-white colobus monkeys and a troop of olive baboons scattered across the road. There is a truly uncharted feel to this southwestern rump of Rwanda. Our guide, Anastase Niyitegeka, said Nyungwe’s river system is the most distant source of the Nile, whose delta is 3,700 kilometres away.

With trackers scanning the trees, we ascended the hill at a near run, through thick branches and over roots swarming with armies of soldier ants. “Maybe you have waited your whole life to see these beautiful animals,” Niyitegeka said. Guests can bring high expectations, but I understood that this was the chimps’ forest, and there was no guarantee of spotting these fast-moving mammals.

Just as I was starting to think it wasn’t going to happen, Niyitegeka pointed to a sunlit cluster of trees. Ten or so chimpanzees were climbing, stretching, jumping, and otherwise living another normal day in the forest, paying us no mind. One grown male knuckle-walked on the forest floor and others lounged in a tree-borne nest.

At Nyungwe, poaching is in steep decline thanks to education and community buy-in programmes, and with conservation efforts redoubled, the chimp population has increased by an estimated 23 per cent since 2014. As with Singita Kwitonda Lodge and Wilderness Safaris’ Magashi, the hotels are taking the lead in this effort. “We have 50 ex-poachers working for us,” said Nyungwe House’s manager, Jacques Le Roux. “They really understand that the forest is sacred.”

On our way out of the park, I stopped at the barebones headquarters for morning tea with the wardens, who shared an almost ubiquitous national exuberance and pride in the parks and their potential. They effused about the 322 species of birds at Nyungwe, the orchids, the canopy walk, the improved conditions of the nearby villages. “We want people to know another side of Rwanda than gorillas,” said Nyungwe’s tourism warden, Thierry Hitimana. And they appreciate the visitors who are helping to bankroll Rwanda’s future. “We hope there will be even more tourism here.”

He just may get his wish. Wilderness Safaris has signed a 25-year lease for the concession at Rwanda’s newest national park, Gishwati-Mukura, where chimps live alongside golden monkeys and other primates. Luxury tourism that’s sustainable is the coin of the realm, and its value is set to grow.

Back in Kigali, I said goodbye to Nsengiyumva and Githaka. We had seen Rwanda’s volcanoes, rain forests, and woodland savanna. We had stargazed from elegant terraces I could not have imagined when I first visited almost a decade ago. This nation is one of the most extraordinary recovery stories of our time. “Rwanda has arrived,” I told Nsengiyumva, and I believed it.

“Modern Rwanda is a thrilling place, but its story is still unfolding,” he replied. “That is what makes it so exciting.”

Getting There

While Ethiopian Airlines offers flights from Delhi to Kigali with a layover in Addis Ababa, Rwand Air offers direct non-stop flights from Mumbai to Kigali.

Kigali

Most visitors to Rwanda will begin and end their trip in the capital, which in recent years has been transformed into a dynamic hub with a thriving food, fashion, and art scene. Stay in the Retreat by Heaven (doubles from INR51,063), a stylish boutique hotel that will unveil eight villas, each with a private swimming pool, later this year.

Akagera National Park

This reserve, which last year was restored to Big Five status, is a 2½-hour drive from Kigali. Wilderness Safaris’ Magashi Camp (doubles from INR83,213, all-inclusive) is the first luxury property in the park. The lodge runs on solar power and has eight glamorous tents overlooking a lake—providing front-row views of elephants, hippos, and spectacular sunsets.

Volcanoes National Park

From Akagera, it’s a short helicopter ride or a five-hour drive to Singita Kwitonda Lodge (doubles from INR2,64,769, all-inclusive) in Volcanoes National Park, home to the country’s storied mountain gorillas. Kwitonda has eight ravishing villas made from glass, brick, and volcanic rock, each with views of the volcanoes.

Nyungwe Forest National Park

From Volcanoes, it’s a 5½-hour drive to One&Only Nyungwe House (doubles from INR1,36,167, all-inclusive), in Nyungwe Forest National Park. Activities at this tea country lodge include an orchid trail, waterfalls, a canopy walk high above the jungle, and—the star attraction—the forest’s resident chimpanzees.

Tours

The Rwandan government has suspended tourist access to Volcanoes National Park, Nyungwe Forest, and Gishwati-Mukura national parks in order to protect mountain gorillas, chimps, and other primates. Researchers from the Leakey Foundation have warned that these animals could be at risk of COVID-19 infection. Once it’s safe to travel again, these Rwandan forests will make for great escapes from your concrete confinement. Moreover, a trip here also aids wildlife conservation efforts.

Related: 7 Reasons We’ll Pick Rwanda Over Any Other African Nation For Our Next Holiday