Seduced by the magnetism of the iconic mountain in Switzerland, I followed a trail along its base. By Sathya Saran

“Are you sure you want to walk the Eiger Trail?” my guide, Roland, asks. “Yes,” I say, emphatically. We have just got off the train at Eigergletscher station and crossed the tiny tracks that take thousands of tourists up and down the steep slope to the highest approachable point on Jungfrau every season. We stand—Roland, my photographer, and I—literally at a crossroads. The Eiger Walk leads one way, the Eiger Trail the other. “The walk is only two kilometres long and easy,” Raymond says softly. “The trail is not easy. It is long, and there are steps.”

“Let’s go,” I say, and step resolutely on the path that starts up the trail, looking up at the Eiger’s North face, looming overhead. It is this mountain that has brought me here, and as I look up, I understand its magnetism. The dark, rough mass of granite, curving inwards to create an amphitheatre of sheer rock, has indeed beckoned many, challenging them and often sending them to their deaths. Ever since I chanced upon Joe Simpson’s account of his audacious attempt on the mountain’s North face in winter, the Eiger has seized my imagination. And while I waited for an opportunity to see it, I read every book on the Eiger, including The White Spider by Heinrich Harrer, which I rank among the best books on mountaineering ever written.

Here I am, at last, preparing for what the write-up called an easy ramble. The Eiger Trail leads you down from the Eigergletscher railway station through six kilometres of gentle slopes, rocky outcrops, and green pasture, to the Alpinglen station below. It should be quite a lark for me, I think, as I have braved steep uphill climbs in the Himalayas on my treks to the Pindari and Sunderdhunga glaciers and to Gomukh, the source of the Ganga.

But the Eiger is a notorious mountain. It shows nothing of its true face to those looking at it from afar. Mountaineers going up the North face encounter streams of icy water carrying stones and rocks, which sometimes come down with lethal force, and at other times, fly straight off the steep slopes into the depths below. Despite being lower than Jungfrau, the Eiger at 3,970 metres has more blood on its rocks than mountains that dwarf it. The slightest of clouds, Harrer notes in his book, “caught in the huge perpendicular upthrust of the Wall’s concave basin can kindle a fearsome storm of hail, snow, and raging winds, while the visitors at Grindelwald, just below there, are sunbathing in their chaise lounges.”

I look up trying to see if indeed there is a storm raging unseen, unheard, high on the mountain. It is a sunny day in November, but I know now that it means nothing. The Eiger, which translates as ‘Ogre’, is not named so without reason. Though today, he seems disinclined to put up a show.

What is putting up quite a show instead is my right leg. A month ago, a nasty fall into a foot-deep pit tore a ligament, or two, and walking has been a challenge ever since. Despite a limp, I have been pushing a few thousand steps on sightseeing walks. But the Eiger Trail seems to have thrown it a serious challenge—the stone and shale-strewn path is veering straight on at a steady incline.

Roland Fontanive is a man of the mountains. Like many of his kind, he is shy of speaking about his countless climbs in the Himalayas of Nepal and the Alps, and it is with much dexterity that I manage to get him talking about his two attempts on Mount Cook in New Zealand, the first thwarted by whimsical weather and the second successful. Having noticed my limp, he has brought along a trekking stick. I feel no shame or hesitation in asking him to hold my hand up the steep slopes, the shifting stones underfoot not only reach me through my thick-soled boots, but seem conspiring to send me spinning.

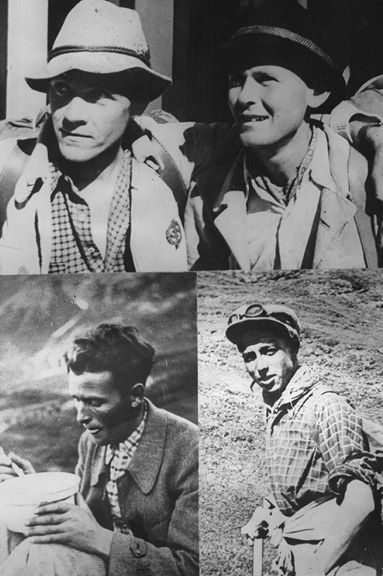

When the going gets especially tough, I think of those who braved the mountain, and the gauntlet it has thrown at me seems a small one. Max Sedlmayr and Karl Mehringer were two young men from Munich, who, without fuss or public announcements quietly made their way up the North face for the first time in 1935, astounding those who watched through telescopes set up at Grindlewald. But the mountain was more than a match. The Ogre had its victims when the two men, after fighting storm and wind, icy weather and mists for five days in the open, disappeared from the mountain face hidden by mist, but their courage would light the way for others.

Anyone who has read about the Eiger will know the story of Tony Kurz, the 23-year-old German who hung by a rope just out of reach for two nights. His friends had died one by one, claimed by rock fall and injury; he alone seemed to defy death even as the night winds stripped him of a glove and frostbite numbed his hand. But he hung at a point where rescuers could not approach him, and when, on the last day, the rope thrown to him fell short, it was too much even for his sturdy spirit to bear. The visual of Tony slumped over the rope, legs dangling in the air, has stayed with me. What, I rebuke myself as my spirit balks at yet another steep incline, is this compared to nights alone on the mountain?

Then, suddenly, we are cresting a slope. A board stands squarely ahead. I grab the excuse to take a break, but need not have worried. As I study the rough drawing of the first successful route up the North face taken by Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer, and Fritz Kasparek in 1938, whose success came after the Eiger had claimed many more lives, Roland pours hot tea sweetened with honey from a flask and holds it out. “Let us celebrate the end of the climb,” he says, eyes twinkling. “From here, it is easy…” then with a quick look at my foot, he adds, “easier”.

Indeed, the path eases out. I take my eyes off the ground to look at the tiny flowers daring the frost that has created patches of ice in the shaded areas. The mountain itself is almost bare of ice. There is no sign of the deadly ice fields that the climbers, one and all, had struggled through in their primitive climbing gear. Today, the mountain has been climbed via innumerable routes by teams from across the world; even though records have been made and broken, the Orge remains unmoved, inviolate. I fail to see its deadly avatar though. There are no waterfalls, or showers of ice. A cloud shields the sun, darkening the face of the Eiger. I shiver in the chill of my bookish knowledge.

It is a long six kilometres. The path winds along, showing no sign of descent. Despite ‘No Cycling’ signs, two intrepid mountain bikers rattle past. Roland warns them, one misplaced tyre could send them hurtling down the craggy slopes! A picnic party watches us, as Roland tells me many prefer to walk up the trail, and others just come halfway to picnic.

Scanning the mountain face, I see the Hinterstoisser Traverse, so named after Kurz’s fellow climber who first solved the problem of an unsurmountable stretch of sheer wall by throwing and fixing a rope across a ledge and traversing to a more accessible route. Forced to turn back when one of the four was injured by a falling rock, the party could not traverse back. Not expecting to return, they had pulled out the rope and the slope was too steep to allow any foothold to fix it from the other end. Hinterstoisser lost his life, but attained immortality thanks to his skills. I imagined the Traverse to be much longer, I muse, but then realise distance is deceptive. The mountain’s crags and crannies cannot be seen with the naked eye.

But it is the Spider I seek, as I walk along. Roland points out the two windows in the rock face, from where the attempts to save Kurz were launched. The window has saved many lives since. The Spider, he says, is high up on the face. Straining and squinting, I follow the direction of his hand. I can see why the Spider provided a deathly challenge. Forcing climbers to squeeze though a chute with a beak-like overhang covering it, the Spider funnels in ice, water, rock, and snow from all sides into the chute. Harrer and others had to fight the cold and wet and slippery surface of a narrow passage to climb to the next level. For the first time in my life, I am glad I am not a mountaineer and will never be tempted to encounter it.

More tea, a sudden fall as my hurt foot buckles under a round stone, a new bump on the knee, and I can see we are on a downward slope. More photographs must be taken—I want to take the Eiger home, since I cannot climb it.

Far below, the Alpinglen station gleams in red and grey. The downward slope is manageable, though there is now the fear of falling again. And my foot has reached its limit. I sing to it softly of Joe Simpson, who, after four days of crawling down a mountain in Peru with a broken shin bone that stuck out at a 45 degree angle, went on to attempt the Eiger’s North face six times and write a book about it. But when, with the station in sight, the path gives way to steep broken steps, my courage fails me. Every step is pure pain. I can feel my foot swollen inside my shoe.

“I told you there were steps,” Roland says, half in rebuke at my foolhardiness.”Not broken steps,” I counter, but the banter distracts me enough to help me navigate safely without tumbling down towards further injury. “But for my injured foot, this is a cakewalk,” I say, as the road broadens and straightens. We have missed our train thanks to me, but “there will soon be another,” of course. So I watch the dusk settle in, wrapping the mountain in dark folds. Beyond, the Jungfrau shines bright, its yellow limestone catching the remaining light. Its slopes always ring with laughter of excited tourists, and in season, skiers rush down its sides. Beside it, the Mönch stands sublime and silent.

Three mountains. The Maiden, bright and fresh; the Monk, silent and serene; and the Ogre, diabolical in its mystery. Why, I ask myself, is it the Ogre that calls to me?

THE DETAILS

GETTING THERE

The easiest way is to fly from Delhi or Mumbai to Bern, or to Zurich, from where you can take a train to Interlaken.

STAY

There are plenty of hotels across price ranges at Interlaken, your base. The choice ranges from the iconic Victoria Jungfrau (from INR 22,000) at the luxury end, to the mid-range Metropole Hotel (from INR 10,000).

EIGER TRAIL

The special train to Jungfrau will take you to the Eigergletscher station, from where you can start the trail or the easier Eiger Walk. The Eiger Trail takes about two and a half hours. The route is fairly clear, but guides can be helpful. July to October is the best time; the trail’s closed in winters. Contact info@jungfrau.ch for guide bookings.

Related: Here’s How To Get Your Adrenaline Fix In Switzerland The Way Ranveer Singh Did!